Twenty years ago, when bassist Marcus Shelby formed a 15-piece jazz orchestra, he began to think big and thematically.

“I have been on a mission for the past 20 years to compose and create music about African-American history,” he says. These pieces have included an oratorio on Harriet Tubman and a suite about Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Civil Rights Movement.

On “Transitions,” released on his own MSO Records, Shelby’s lush arrangements of classic tunes by Charles Mingus, Duke Ellington, and Cole Porter frame the album’s centerpiece: “Black Ball: The Negro Leagues and the Blues,” his smart, slick and soulful four-part suite inspired by the history of Negro League Baseball. Here, Shelby merges his mission with his two driving passions—jazz and baseball.

While working on my next column for Jazziz magazine, I spoke with Shelby about these passions.

Have you always been a baseball guy? Did you play?

I have always loved baseball. I played little league up to high school, but later focused on basketball as I entered my junior and senior years. I actually played basketball, football, baseball, and ran track. I received a full ride basketball scholarship to attend Cal Poly (SLO) in 1984 and put my bats and gloves down. It was the Michael Jordan effect. Most black kids my age at that time were mesmerized by Jordan and basketball became more attractive. Perhaps it was the opportunities, like scholarships, that basketball provided. It was also less expensive for low-income communities. You just needed a bucket and ball. Baseball, you needed all the equipment and 18 guys, plus a well-groomed field. Nonetheless, I played outfield and also pitched. Now I play catcher because I’m mostly playing with young kids and that’s the one position you need someone who is not afraid to get hit.

After playing basketball for four years at Cal Poly, something strange happened that altered my course. I went to a Wynton Marsalis concert in Sacramento at the Radisson Inn, in 1988, and I lost my mind. The band included Marcus Roberts, Bob Hurst, and Jeff “Tain” Watts. You see, I also played bass in high school but had no dreams of becoming a professional musician. After seeing Marsalis and understanding that my sports career was coming to an end, I was inspired. I found an old bass and began playing again. I fell in love with music! Specifically blues and swing. I left San Luis Obispo after graduation in 1990 and went to LA where I met Billy Higgins and joined the World Stage Jazz Workshop. I got a job at Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena which is why I went to LA. I didn’t really want a “real” job but that was my reality in 1990. Soon after landing in LA, I applied and received a scholarship to attend Cal Arts and study bass with Charlie Haden and composition with James Newton. Goodbye JPL and electrical engineering. Things moved fast. I started a group called Black/Note that featured drummer Willie Jones III and trumpeter Gilbert Castellanos. We all went to Cal Arts. We signed a record deal with Columbia Records, toured with Wynton Marsalis as his opening act, and my life became only music for the next 6 years. I did not follow baseball as closely. I think it was because I was surrounded by nothing but Dodger fans.

When did that change?

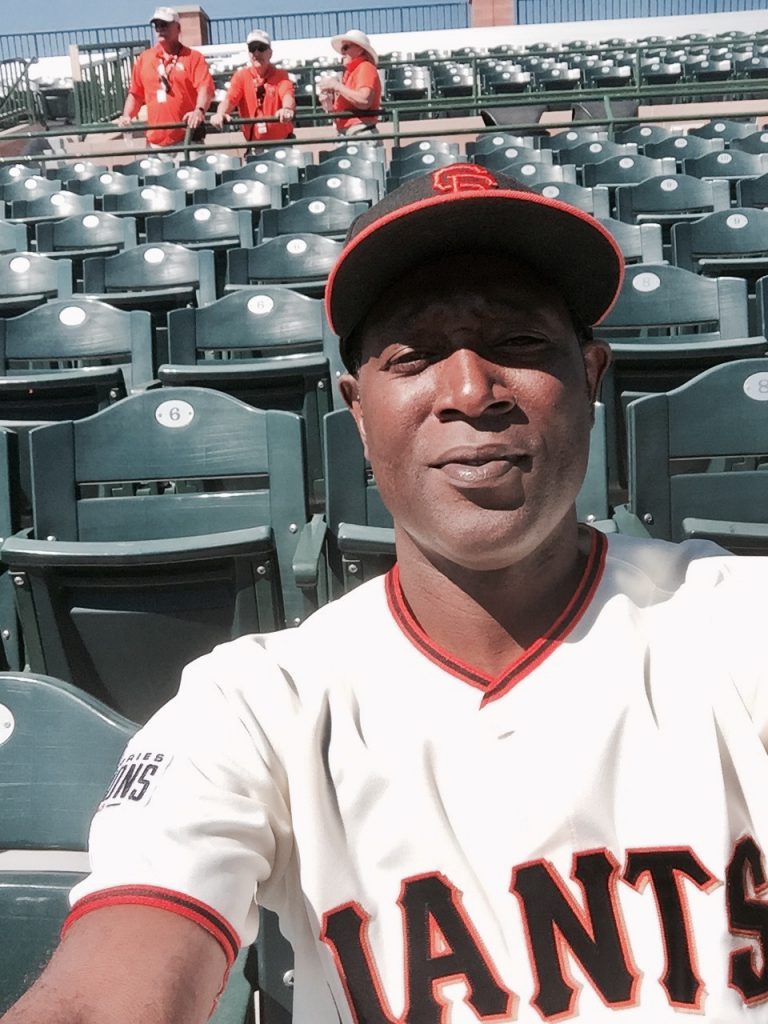

Fast forward to 1996, when I moved to San Francisco, I became interested in baseball all over again having settle into a career as a musician. It was the Giants and Barry Bonds that did it. San Francisco is a baseball town. Like St. Louis, Chicago, and Philly, baseball is part of the civic culture. It’s hard to live here and not be aware of what’s going on with the Giants. All of this brought me right back to my love of the game. Since I’ve been in San Francisco (23 years now), I have been active over the past 5 years working with kids on simple baseball skills, organizing pickup games at my daughter’s school, and just having fun getting to know people by inviting them to play catch. I carry gloves, balls, bats, bases, and other equipment in my car and will play catch with anyone willing to. I have 2 daughters (9 and 16). My 9-year old daughter plays baseball. We play every day. Before school and after school. Weekends too. It’s our common passion. We go to 50 Giants games a year as we live 10 minutes from Oracle Park (former AT&T park). I attend Spring Training in Arizona every Spring. I’m good friends with our flagship station (KNBR) and have been a guest on that radio program (Talking Baseball with Marty Lurie) twice, talking about the Negro Leagues and related subjects. So that’s it in a nutshell. I started off has a hard core athlete in four sports, became a full time musician, and have married my two interests together creating music about the history of baseball.

What gave you the idea for this suite?

I have been on a mission for the past 20 years to compose and create music about African American history. I’ve written an oratorio on Harriet Tubman, a suite about Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Civil Rights Movement, Port Chicago, the Prison Industrial Complex, and other collaborative projects about black history through plays, ballets, and films. The Negro Leagues have been on my mind for years. Back in 1993, I wrote a piece called “The Ballad of Josh Gibson,” but I was not at a point where I truly understood the history of the Negro Leagues, its impact on the Civil Rights Movement, and certainly not all of the colorful characters that make up the rich history—including Fleetwood Walker, Rube Foster, Effa Manly, Satchel Paige, Cool Papa Bell, and of course Jackie Robinson.

I have had my big-band orchestra now for 20 years. I have great support from my artistic home the Yerba Buena Gardens Festival and also from SF JAZZ. This support has allowed me to create a piece about the Negro Leagues where I was able to spend three years researching the subject, attending conferences, interviewing surviving Negro League players, reading all the books, and sufficient time to compose and orchestrate.

Are there specific musical aspects that relate in some specific way to the sport of baseball?

I have a section that is called “At Bat” that is the re-creation of an at-bat, and features three clowns that I employ throughout the suite. In this case, the music follows the action which ends up being a strikeout; this starts an argument between the batter and the umpire (both played by clowns) and turns into an aria sung by the umpire.

I am very interested in the sound of baseball and have tried to create the essence of a crack of bat, or the blues holler of the ump, or the space between action which baseball and music use to create tension and release. Most of these reincarnations are found in the full outdoor presentation of our piece “Black Ball: The Negro Leagues and the Blues” which incorporated clowns and actors. Our recording is a mini-suite of four pieces that frame the important cities that birthed black baseball—Chicago, NY, Pittsburg, and Kansas City.

Can you tell me more about your research for this suite?

I spent three years researching “Black Ball: The Negro Leagues and the Blues”. This research included joining SABR (Society of Baseball Research), attending conferences, reading no less than 30 books, watching films, pretty much living on YouTube, making in-roads with the SF Giants organization, studying all music recorded that I could find about baseball, and being active on online forums to obtain information. I had generous support from the MAP fund, the Yerba Buena Gardens Festival, and SFJAZZ.

What did you learn in doing that research?

I learned that the real hero of Negro League baseball was Rube Foster. He taught black people to be self-sufficient and to build their own infrastructure to support segregated baseball. This including owning your own fields, booking agencies, concessions, hotels, travel, and of course teams. I believe he died of a broken heart because of the collapse of this solidarity.

Do you see a parallel between Negro leagues and pre-integration music scenes?

Absolutely. That inspired the suite in a way—the parallel history of the birth of blues music and the birth of the Negro Leagues. The first black baseball players in MLB was Fleetwood Walker and his brother Welday Walker. Fleetwood played for the Toledo Blue Stockings but was banned in 1884 because of the most popular player at the time, Cap Anson, and his reluctance to play with black players. This ban of course lasted until 1947, when Jackie Robinson got signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Rube Foster started the first organized Negro League in 1920, right about the same time Gertrude Ma Rainey, Alberta Hunter, Bessie Smith, Sara Smith, and others made the first blues recordings and toured the infamous wheel which ran through the south, Midwest, upper south, and parts of the south east. Barnstormin’ Negro League baseball teams employed the same traveling routes, stayed at the same hotels, ate at the same homes, and in many cases were booked by the same agents. This would be true all the way up to the 1960s. If you were Nat King Cole Jr., or Ella Fitzgerald, or Satchel Paige, or Toni Stone (second basewoman for the Indianapolis Clowns in 1962) you probably stayed at the Lorraine Hotel in Memphis Tennessee as that was the only place a black artist or entertainer could stay during segregation. The impulses between Negro League players and early “jazz” musicians were the same. The style of baseball was loose, fast, and furious. Style was of the essence. Same as in music. The cultural connections that informed both the sport and the music are unmistakable such as their “lingua franca” and improvisational necessity.

The live presentation of this music went even further, in an attempt to re-created the environment of a Negro League baseball park. How did you do that?

When we performed “Black Ball: The Negro Leagues and the Blues” at the Yerba Buena Gardens Festival September 2018, we performed the suite outside in a park and borrowed from the recorded history of what happened at Negro League parks or at least parks where Negro League teams played (such as Comisky Park in Chicago). This included using clowns that “shadow-balled” and recreated infield practice, We recreated a live radio show that interviewed black luminaries like Satchel Paige, Jackie Robinson, Effa Manly, and Rube Foster, and my big band orchestra performed the suite with three vocalists and four actors to bring interesting aspects of the history to life though monologues and original and re-arranged songs.

In what way were the four cities—Pittsburgh, New York, Chicago, Kansas City—central to the Negro leagues, and do you see a parallel there with jazz in those towns?

I highlight these four cities in my suite because they were most central to the history of Negro League Baseball. The first Negro League team was the New York Cubans. New Yorkhad a big influence on Negro League baseball because of its market size and also its large black population that included Afro Latinos. I’d also include one of the most influential owners Effa Manly who ran the Newark Eagles and was central to Negro League baseball in New York. Chicago is where the Negro Leagues as an initial entity began through the efforts and leadership of Rube Foster, who migrated from Texas to Chicago (like so many other musicians who traveled up the Mississippi River like King Oliver and Louis Armstrong). Rube Foster first started the Chicago American Giants.Pittsburgh was home to the rebirth of Negro League baseball in 1931 because of the numbers runner Gus Greenlee, who owned the Crawford Grill (and managed several boxers). He put together a tenacious team called the Pittsburg Crawfords that sported a roster that included Cool Papa Bell, Josh Gibson, Judy Johnson, Sam Bankhead, and the great Satchel Paige. In 1933, Greenlee started the Negro League Allstar game that would ultimately save the Negro Leagues from financial ruin until World War 2 started, which actually in a strange way helped the Negro Leagues (and MLB) due to the fact people had jobs. Kansas Cityis where the most legendary team is from—the Kansas City Monarchs, which had Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, and Jackie Robinson at some point on their roster. The Kansas City Monarchs are also the first team black or white to use night lights to be able to perform at night.

In all four cities, we also see independent musical styles that were influenced by factors of migration early on. New York City was experiencing a population boom that defined life, surrounded by subways, cultural diversity, street cars, and city sounds. Chicago saw a migration from the South, such as New Orleans, Memphis, and Texas, and with that they brought with them a tinge of the blues that would define Chicago “jazz”. Same with Kansas City, which birthed the Count Basie Orchestra. I love the story of Pittsburgh, and how families like Josh Gibson’s family migrated there like many other black families that produced artists like Ahmad Jamal, Art Blakey, Billy Eckstein, Kenny Clarke, Paul Chambers, Ray Brown, Earl “Fatha” Hines, and Errol Garner. There is a consistency of refined musicmaking in all of these cases. Pittsburgh, a steel town full of sand lots, is a perfect example of the cultural simpatico between baseball and music.

Obviously, this concept has to do with many things, especially African American history. But do you also see a natural affinity between playing jazz and playing baseball, things that are inherent in the doing of both?

I see some connections. If you watch players like Mookie Betts, Dee Gordon, Billy Hamilton, Yasiel Puig, Jose Altuve, Javier Baez, Lorenzo Cain, or even Cody Bellinger, you will see the spirit of “jazz” being played out every time. These players play in the moment. They read the situation and respond. I wouldn’t say baseball has the same rhythm as “jazz”, but it does swing and it grooves. Watch the rhythm and motion between a pitcher and a catcher. It’s critical that it has rhythm or the pitcher will be rattled. Watch any infield practice. Same thing. There is a flow and rhythm to it: You have to be ready because it’s different every time a fast hop is coming at you, just like being fora bassist being in the middle of walking rhythm changes.

Also, baseball takes patience. I’m old school. No clocks, please. Jazz, of course, is a patient art form with little gratification that is quick and easy. A good composition is an experience that involves a group effort in which you have leads and you have role players.—just like in baseball. It unfolds over time and can not be reduced to a bite size understanding. You either like “jazz” or you don’t. You either like baseball or you don’t. There really isn’t any way to dumb down the two, to make them more accessible, and I’m OK with that.

Were your jazz orchestra a baseball team, what position would you play?

I think about this question every day, as I’m always trying to learn the values of baseball by watching games,” he says. “I would certainly be the catcher. As a bass player, I think the catcher has the equivalent role: steady and consistent; involved in every pitch; controlling the tempo by calling the game; rarely the front-person but in the center of the action and comfortable with that role.